Thomas Cromwell Controversies

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Historical Controversies about Sir Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex Click EasyEdit to add this page! (Don't see the EasyEdit button above? <a href="/#signin" target="_self">Sign in</a> or <a href="/accountnew" target="_self">Sign up</a>.) |

| Questions - and some answers: - If Cromwell fell from favour because of the Anne of Cleves marriage, as most believe, why did Henry title him Earl of Essex in April 1540 - several months AFTER the marriage had been finalized and while negotiations for divorce were underway? It is even said that the King kept Cromwell alive in prison to work on the divorce. -Perhaps as Alison Weir suggests in her "Six Wives of Henry VIII", he only kept him alive to anull the marriage to Anne of Cleves, once that was completed Henry took his revenge? "Henry lured Thomas into a false sense of security, he hoped to exact deadly revenge, which would be as unexpected as deadly." - If Cromwell was executed because his government policies angered the king, as has been alleged, why did Henry give his voluntary approval to ALL of Cromwell's legislation? - If his enemies were in the ascendancy, why had Henry only recently shown Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of Norfolk(Cromwell's great enemy) open favour? After all, Norfolk had just been sent abroad on diplomatic work - away from the king. - He was not accused of misleading Henry on matters of policy, he was not held responsible for the disastrous marriage, and he was not charged with leading England into an unwanted Lutheran alliance . The bulk of his attainder was HERESY, plus he was charged with illegally selling export licenses and granting passports and commissions without royal knowledge. Also shortly after his arrest, incriminating letters to Lutherans were found in Cromwell's home, placed there by agents of the Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk; they were so inflammatory that the king was outraged. Cromwell's name, Henry swore, would be abolished forever. Had Thomas become just another victim of factional manoeuvring just as he had done himself to others many times before? |

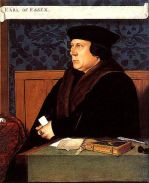

| Thomas Cromwell, perhaps not such a villain? [Quoted - Source: [from Times Online] by Hilary Mantel - author of the Novel "Wolf Hall" - see video clip below] "Every day of Cromwell’s political life was a fight — not just because of what he stood for, but because of who he was. He came from a humble background, and historians as well as contemporaries seem to have held that against him. He is accused of hounding to his death the saintly Thomas More — though from our perspective, the heretic-hunting More doesn’t look so saintly, and it was the king, not Cromwell, who wanted More dead. In novels, and in plays and films such as A Man for All Seasons, Cromwell is a cold Machiavellian, or a desiccated administrator. His character has been painted as so comprehensively black that any reasonable person would think — as I did — that there must be another side to the story. .....When I set out to find Cromwell, I discovered a man who succeeded by toughness and unremitting hard work, by ingenuity, suppleness and flair; a gregarious man, generous and cultured, good at making friends and watchful of their interests. There was a touch of the mafia boss about him: once you were part of the Austin Friars family, you would be protected, made useful and often made rich. He had a strong sense of purpose and an armoured self-belief. I was enthralled by watching his acute political instinct in operation as he picked his way from crisis to crisis, and puzzled by a man who seemed capable of both great personal kindness and utter ruthlessness. There are usually at least two ways to read a communication from the dead. In Cromwell’s case, many scholars choose to put the worst construction on every piece of documentary evidence left to us. The historian Geoffrey Elton was emphatic about Cromwell’s status and importance: “Wherever one touches him, one finds originality and the unconventional.” But as many of today’s Tudor historians were trained by Elton, they have to define themselves against him: Cromwell at the moment is out of fashion, and his biographies tend to rehash old clichés and prejudices. They say “Thomas Cromwell” on the cover, but there isn't a man inside. The flesh-and-blood reality is elusive. His fingerprints are all over the laws and public acts of Henry’s reign. His private life is largely hidden. It seemed to me there was a challenge. There might not be the personal material for a good biography. But could a novelist reconstruct him, by applying an informed imagination? For the decade of his power, the papers of the reign — the historian’s basic source — are almost a history of Cromwell. Luckily, he filed almost every letter ever sent to him. What sort of a man did they think they were writing to, these correspondents from all over Europe? I saw him, initially, through the mirror of other people’s perceptions. Then I tried — because this is what a novelist can do — to step through the glass and see the Tudor world from behind his eyes. .... he was talent-spotted by Thomas Wolsey, England’s cardinal and lord chancellor, the brilliant, flamboyant, charismatic man who was the country’s alter rex: the other king. They became close friends; he was Wolsey’s “entirely beloved Cromwell”. In the dark days of Wolsey’s fall, one of the cardinal’s servants, George Cavendish, came across a spectacle that dismayed him: Cromwell, leafing through a prayer book and crying. It was a sight never seen again. He was not given to the open display of emotion, and we will never really understand his religious position. Some historians take him to be a cynic who used religion as an instrument of policy, though it was he who put the English Bible in every church. I take his reformist convictions to be sincere. But you needed a sense of irony to work with him. The Spanish ambassador described how one day, when spinning him a particularly unlikely line about the king, the minister simply burst out laughing. .......After England’s break with Rome, nobody was closer to the king.  Holbein’s portrait of Cromwell dates from about this time. He is a grim presence, pushed into a small space, as if only by wedging him between two tables could the painter keep him from pounding off to get on with his day. He was, one of his friends said tactfully, “inclined to be fat”, but he must have been a very fit man to have shouldered his workload. In conversation, the Spanish ambassador said, Cromwell was animated and witty. His eyes were always on your face; he read you like a book. Holbein’s portrait of Cromwell dates from about this time. He is a grim presence, pushed into a small space, as if only by wedging him between two tables could the painter keep him from pounding off to get on with his day. He was, one of his friends said tactfully, “inclined to be fat”, but he must have been a very fit man to have shouldered his workload. In conversation, the Spanish ambassador said, Cromwell was animated and witty. His eyes were always on your face; he read you like a book.Henry made Cromwell his deputy for the administration of his new Church of England, and put him in charge of freeing up the immense wealth of England’s monasteries and diverting it into the crown’s pocket. Henry was good at spending money, and Cromwell was good at making it. He costed out Henry’s whims and made them reality. But political outcomes are hard to calculate, and Cromwell was a gambler who took huge risks — particularly when the king handed him the job of getting rid of his second wife. He saw Anne Boleyn in, and saw her out, orchestrating an elaborate plot in which warring factions agreed to work together, each thinking they would come out on top; in the end, the winner was Cromwell. When Jane Seymour became queen, Cromwell married his son, Gregory, to her sister. The blacksmith’s boy, the runaway from Putney, had succeeded in becoming very nearly royal himself. In writing about Cromwell, I came to admire him, but it’s not part of my intention to whitewash him. He operated in conditions where England was isolated, a pariah state, and vulnerable to invasion. He was a formidable interrogator, and he tortured people he thought a threat to national security. At the same time — these are the contradictions a novelist must work with — he was a humane man with a radical social vision. His circle of reformers plotted sweeping law reforms, educational initiatives, and the tentative beginnings of state responsibility for the poor and unemployed. If he had lived and been able to push through his ideas, England would have been a fairer country. But the mass of people, deeply conservative in their instincts, didn’t begin to grasp this. Far from being glad that an ordinary man was close to the king, they read Cromwell’s career as unnatural; kings should be advised by noblemen. How had this upstart got so much power? He must be a sorcerer. Wolsey, people said, had left him an enchanted ring, which he used to control the king. When revolt broke out in the north in 1536, it was Cromwell, not Henry, who was the target of the people’s anger. He could live with his black reputation. It was more dangerous that conservative churchmen and the old nobility envied and hated him. They saw an aristocracy of talent replacing them; Cromwell had a knack of identifying able men from any background, and England’s brightest and best went to work for him. In the summer of 1540, his chief enemies — Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester — managed to join forces and bring him down. He was arrested at a council meeting and bundled off to the Tower. Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury,reminded Henry: “He was such a servant . . . in wisdom, diligence, faithfulness, and experience, as no prince in this realm ever had . . . Who shall Your Grace trust hereafter, if you might not trust him?” Henry kept the doomed man alive for some weeks to work on the evidence for yet another divorce, from Anne of Cleves. On the day of Cromwell’s beheading, Henry married Norfolk’s niece, Katherine Howard. In less than two years, Katherine, wife number five, followed Cromwell to the block. When Cromwell fell from power, the king took everything — lands, title, the house at Austin Friars. Within weeks he was lamenting that he had been tricked into killing his most loyal servant. He regranted to Gregory Cromwell his title of baron. Oliver Cromwell, however, descends not from Gregory but from Thomas Cromwell’s sister Katherine. It is amazing that one obscure family should have had such a galvanising effect on English history. The whole of the first Cromwell’s story is supremely unlikely, and this is what drew me to the spectacle of his rise and rise. Like Henry himself, he is less like a historical figure than a figure from myth, an adventurer, a trickster, a chancer; one of those strange beings who transcend anything that could have been predicted for them, and who change the shape of the world before they leave it." |

<embed allowfullscreen="true" height="350" src="http://widget.wetpaintserv.us/wiki/thetudorswiki/widget/youtubevideo/744f3252c0284edc41901010acb2faff0f222ea2" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="425" wmode="transparent"/> Tudor Historians Hilary Mantel and David Starkey discuss the shared subject of their new books - Henry VIII. Filmed in location in the Upper Bell Tower in the Tower of London: the scene of John Fishers imprisonment prior to being martyred. |

LINKS:

| SOURCES: |