TRIAL of Anne Boleyn

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

See also :

|

| An Unprecedented Conviction | ||||||||

Earlier English Queens had been unfaithful and done treasonable acts, notably: -

"Nor had this happened in France, where in 1314, three french princesses, among them the wife of the heir to the throne were found guilty of committing adultery; but while their lovers were savagely butchered on the scaffold, they themselves were condemned only to divorce and imprisonment." [source: Alison Weir The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn 2010] | ||||||||

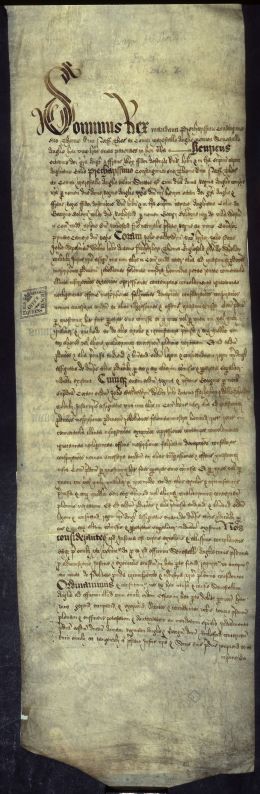

| The Indictment | ||||||||

Source : <a class="external" href="http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=75430" rel="nofollow" target="_blank" title="British History online - primary sources">British History online - primary sources</a> Indictment found at Westminster on Wednesday next after three weeks of Easter, 28 Hen. VIII. before Sir John Baldwin, &c., by the oaths of Giles Heron, Roger More, Ric. Awnsham, Thos. Byllyngton, Gregory Lovell, Jo. Worsop, Will. Goddard, Will. Blakwall, Jo. Wylford, Will. Berd, Hen. Hubbylthorn, Will. Hunyng, Rob. Walys, John England, Hen. Lodysman, and John Averey; who present that whereas queen Anne has been the wife of Henry VIII. for three years and more, she, despising her marriage, and entertaining malice against the King, and following daily her frail and carnal lust, did falsely and traitorously procure by base conversations and kisses, touchings, gifts, and other infamous incitations, divers of the King's daily and familiar servants to be her adulterers and concubines, so that several of the King's servants yielded to her vile provocations; viz., on 6th Oct. 25 Hen. VIII., at Westminster, and divers days before and after, she procured, by sweet words, kisses, touches, and otherwise, Hen. Noreys [[[Henry Norris]]], of Westminster, gentle man of the privy chamber, to violate her, by reason whereof he did so at Westminster on the 12th Oct. 25 Hen. VIII.; and they had illicit intercourse at various other times, both before and after, sometimes by his procurement, and sometimes by that of the Queen. Also the Queen, 2 Nov. 27 Hen. VIII. and several times before and after, at Westminster, procured and incited her own natural brother, George Boleyn, lord Rocheford, gentleman of the privy chamber, to violate her, alluring him with her tongue in the said George's mouth, and the said George's tongue in hers, and also with kisses, presents, and jewels; whereby he, despising the commands of God, and all human laws, 5 Nov. 27 Hen. VIII., violated and carnally knew the said Queen, his own sister, at Westminster; which he also did on divers other days before and after at the same place, sometimes by his own procurement and sometimes by the Queen's. Also the Queen, 3 Dec. 25 Hen. VIII., and divers days before and after, at Westminster, procured one Will. Bryerton [[[William Brereton]]], late of Westminster, gentleman of the privy chamber, to violate her, whereby he did so on 8 Dec. 25 Hen. VIII., at Hampton Court, in the parish of Lytel Hampton, and on several other days before and after, sometimes by his own procurement and sometimes by the Queen's. Also the Queen, 8 May 26 Hen. VIII., and at other times before and since, procured Sir Fras. Weston [[[Francis Weston]]], of Westminster, gentleman of the privy chamber, &c., whereby he did so on the 20 May, &c. Also the Queen, 12 April 26 Hen. VIII., and divers days before and since, at Westminster, procured Mark Smeton [[[Mark Smeaton]]], groom of the privy chamber, to violate her, whereby he did so at Westminster, 26 April 27 Hen. VIII. Moreover, the said lord Rocheford, Norreys, Bryerton, Weston, and Smeton, being thus inflamed with carnal love of the Queen, and having become very jealous of each other, gave her secret gifts and pledges while carrying on this illicit intercourse; and the Queen, on her part, could not endure any of them to converse with any other woman, without showing great displeasure; and on the 27 Nov. 27 Hen. VIII., and other days before and after, at Westminster, she gave them great gifts to encourage them in their crimes. And further the said Queen and these other traitors, 31 Oct. 27 Hen. VIII., at Westminster, conspired the death and destruction of the King, the Queen often saying she would marry one of them as soon as the King died, and affirming that she would never love the King in her heart. And the King having a short time since become aware of the said abominable crimes and treasons against himself, took such inward displeasure and heaviness, especially from his said Queen's malice and adultery, that certain harms and perils have befallen his royal body. And thus the said Queen and the other traitors aforesaid have committed their treasons in contempt of the Crown, and of the issue and heirs of the said King and Queen. | ||||||||

"Sir Christopher Hales, Attorney General, was the chief prosecutor for the King. Hales was educated at Gray's Inn and was a member of a family of lawyers. He rose to be Attorney General after having served as Solicitor General, and two months after the trial of Anne Boleyn he succeeded Thomas Cromwell as Master of the Rolls."' He had previously represented the Crown at the trials of Cardinal Wolsey, Sir Thomas More, and Bishop Fisher. Like Audley, he performed his duties conscientiously and with neither undue harshness nor undue charity. Cromwell, who also had legal training, assisted with the prosecution. The words spoken by these men in prosecuting the case have not been preserved, but it is known that they presented no witnesses. In this sense the entire case for the prosecution was much like a prosecutor's opening statement: describing the evidence and the results of the investigation but offering no "live" evidence to support the conclusions. In the usual trial of this nature, someone whom the powerful wanted destroyed was accused of having said or done something that according to law was treason, and witnesses were found to swear to it. In this case, however, treason was constructed from the words that the Queen admittedly had spoken; these words were embellished until they constituted treason under three different statutes. Anne had discussed marriage with Norris, and this could not be denied; but alone it meant nothing. It was reasoned, however, that since she had spoken of marriage to Norris, she wanted to marry him. It followed that she must have wanted the King dead, and therefore she must have contrived to kill him. This last step in the reasoning may have been unnecessary. To wish the King dead in itself could be treason. Under the most important of the treason statutes, the 1352 law of Edward III, . it was treason to "compass ... or imagine . . . the death of the King, his consort, or his eldest son. ' Some dispute has existed whether this statute required some overt act or whether it allowed the punishment of treason committed by words alone. Authority does support the view that even by the end of the fifteenth century, treason by words alone was sufficient. Thus even under the 1352 statute, the words of Anne Boleyn, if construed as argued by the prosecution, would support a charge of treason..... After having been presented with the case for the King, the peers heard Anne Boleyn's defense. She was unassisted, and there is no indication that she made what would have been a futile request for counsel. The Queen might have been permitted to present the testimony of others on her behalf, but in light of her lack of knowledge before the trial of the specific charges against her and her imprisonment prior to trial, the granting of this request would have done her little good... the defense in the trial of Anne Boleyn consisted only of her own speech, in which she eloquently protested her innocence of all the charges. Because Anne had not seen the indictment in advance, she could not reply to each specific charge by producing an alibi for each date. Despite her lack of evidence, Anne's defense persuaded many spectators, including magistrates of London, that there was no evidence against her, but that it had been decreed that she must be disposed of once and for all." [Source: William and Mary Law Review] | ||||||||

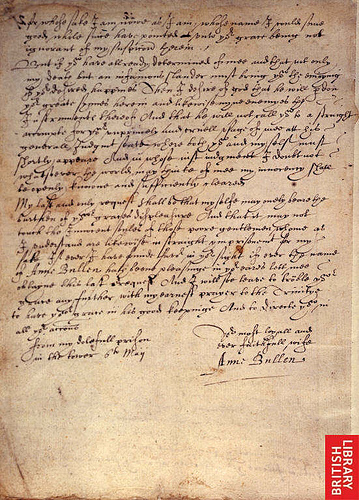

| Anne's Letter ? | ||||||||

| Arrested May 2nd, 1536, 4 days later it was said that Anne sent a letter to Henry. Allegedly found in Thomas Cromwell's papers after his execution in 1540. Scrawled across the top in what seems to be Cromwell’s handwriting: “To the King from the Lady in the Tower”. The letter is disputed by most historians saying that the handwriting isn't her usual neat style and she refers to herself as Anne Bullen, however, some historians believe it mirrors her psychology and is a copy of an original. Notably, Jasper Ridley who rejected the letter as “a forgery, written in the reign of her daughter, Elizabeth,” in his 1984 biography Henry VIII, he later changed his mind in The Love Letters of Henry VIII (1987), in which he claimed every element of the letter fits with what we know of Anne’s psychology at this stage in her imprisonment.

| ||||||||

The Trials of Anne and the five men | ||||||||

"On Tuesday, 9 May [1536] the sheriffs of London were ordered to assemble the next day a grand jury of 'discreet and sufficient persons' to decide prima facie on the offences alleged at Whitehall and Hampton Court. Despite the short notice the sheriffs produced a list of 48 men, three quarters of whom, as instructed, turned up at Westminster before John Baldwin, chief justice of the common pleas, and six of his judicial colleagues". John Baldwin was Henry Norris' brother in law and puzzlingly not the obvious choice.

Mark Smeaton confessed to adultery, but pleaded not guilty to the rest of the charges; Henry Norris, Francis Weston and William Brereton pleaded not guilty to all.

Even where a jury was not loaded in advance, defendants in a Tudor criminal trial - even more, a state trial - were at an enormous disadvantage. They had no advance warning of the evidence to be put, and since defence counsel was not allowed, they were reduced to attempting to rebut a public interrogation by hostile and well-prepared Crown prosecutors determined not so much to present the government case as to secure a conviction by fair questions - or foul.

Anne and her brother George were tried on Monday, 15 May [1536].

Their uncle Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk sitting as Lord Steward with his son [[[Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey|Henry Howard]]] at his feet plus a jury of 26 peers assisted by the chancellor and the royal justices. Anne sat in chair provided, raised her right hand when called and pleaded 'not guilty' to the indictment. The jury deliberated under the watchful eye of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk.

"Because thou has offended our sovereign the king's grace in committing treason against his person and here attainted of the same, the law of this realm is this, that thou has deserved death and they judgement is this: that thou shalt be burned here within the Tower of London, on the Green, else to have thy head smitten off, as the king's pleasure shall be further known of the same". Anne spoke up saying , as God was her witness she had done the King no wrong except for her jealousy.

Tudor criminal trials were more about securing condemnation by due process than evaluating evidence, but two grand juries, a petty jury and a jury of peers sitting twice rejected the defence presented by Anne Boleyn and her alleged lovers. ..... When the duke of Suffolk's 'guilty' completed the Rochford verdict, 95 successive voices had spoken against them. Ten years later, even Henry himself would admit that a victim in the Tower had no defence against false evidence." [source: Eric Ives' Life and Death of Anne Boleyn]

|