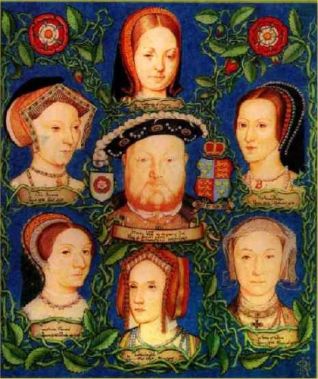

Letters from the Queens

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Lose his heart, lose your head!

Source: <a class="external" href="http://englishhistory.net/tudor/letters.html" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">http://englishhistory.net/tudor/letters.html</a>

Get his heart, gain the world..

Lose his heart, lose your head!

The following are letters from the Queen's written to the King.

See also:

|

| Background | Letter |

| This is the last letter Queen Katherine of Aragon wrote to Henry. Its magnanimity is proof that the queen's much-vaunted piety was sincere. However, she was not averse to a few rebukes. Henry had treated her horribly and she had not seen their daughter for years. But Katharine's capacity for forgiveness was great, as was her self-delusion; in this letter, she again attributes his love for Anne Boleyn to mere physical desire. Henry openly celebrated her death and she was buried as Dowager Princess of Wales in Peterborough Cathedral. In light of this, the last line of her letter becomes especially tragic. While she may have desired a visit with him above all else, Henry was only too happy to learn of her death. It is probable, too, that his harsh treatment of Katharine hastened her decline. | My most dear lord, king and husband, The hour of my death now drawing on, the tender love I owe you forceth me, my case being such, to commend myself to you, and to put you in remembrance with a few words of the health and safeguard of your soul which you ought to prefer before all worldly matters, and before the care and pampering of your body, for the which you have cast me into many calamities and yourself into many troubles. For my part, I pardon you everything, and I wish to devoutly pray God that He will pardon you also. For the rest, I commend unto you our daughter Mary, beseeching you to be a good father unto her, as I have heretofore desired. I entreat you also, on behalf of my maids, to give them marriage portions, which is not much, they being but three. For all my other servants I solicit the wages due them, and a year more, lest they be unprovided for. Lastly, I make this vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things. Katharine the Quene. |

| Seventeen of Henry VIII's famous love letters to Anne Boleyn exist; they can be viewed at the Vatican Library. However, only one of Anne's love letters to the king has survived. It is undated, but its contents place it in late summer/early autumn of 1526. How? She thanks the king for personally appointing her a maid of honor to his queen, Katharine of Aragon, but also - and more importantly - she acknowledges the king's serious declaration of love for her. As students of Anne's life know, this subtle but vital shift in their relationship occurred in summer 1526. We also know that she returned to court as a maid of honor to Katharine of Aragon at the same time. Interestingly, this letter reveals that Anne owed her position at court entirely to the king's favor. This is believed to be the first love letter Anne wrote to Henry, and is rarely included in any biography of the queen. However, its authenticity is not in serious doubt. One should remember that Henry's brief relationship with Anne's sister, Mary Boleyn, had only ended a year before (in July 1525.) On 4 March 1526, Mary gave birth to a son called Henry, widely assumed to be the king's son. Anne's feelings about this awkward situation were never made clear, but she was not close to her sister. Please note that Anne spelt her surname 'Bulen' in this letter. This is the third variation of the name I've found | Sire, It belongs only to the august mind of a great king, to whom Nature has given a heart full of generosity towards the sex, to repay by favors so extraordinary an artless and short conversation with a girl. Inexhaustible as is the treasury of your majesty's bounties, I pray you to consider that it cannot be sufficient to your generosity; for, if you recompense so slight a conversation by gifts so great, what will you be able to do for those who are ready to consecrate their entire obedience to your desires? How great soever may be the bounties I have received, the joy that I feel in being loved by a king whom I adore, and to whom I would with pleasure make a sacrifice of my heart, if fortune had rendered it worthy of being offered to him, will ever be infinitely greater. The warrant of maid of honor to the queen induces me to think that your majesty has some regard for me, since it gives me means of seeing you oftener, and of assuring you by my own lips (which I shall do on the first opportunity) that I am, Your majesty's very obliged and very obedient servant, without any reserve, Anne Bulen. |

| Jane Seymour was the mother of Henry VIII's longed-for heir, Prince Edward Tudor. He was born on 12 October 1537, and this letter was immediately sent to the Privy Council by the queen. Jane may not have personally composed the letter; however, it was sent in her name and sealed with her signet. Though she died of puerperal fever twelve days after the birth, she was not immediately ill. In fact, the letter muses upon the precariousness of the infant prince's health. This sentiment was understandable enough in an age of high infant mortality. | Right trusty and well beloved, we greet you well, and for as much as by the inestimable goodness and grace of Almighty God, we be delivered and brought in childbed of a prince, conceived in most lawful matrimony between my lord the king's majesty and us, doubting not but that for the love and affection which you bear unto us and to the commonwealth of this realm, the knowledge thereof should be joyous and glad tidings unto you, we have thought good to certify you of the same. To the intent you might not only render unto God condign thanks and prayers for so great a benefit but also continually pray for the long continuance and preservation of the same here in this life to the honor of God, joy and pleasure of my lord the king and us, and the universal weal, quiet and tranquility of this whole realm. Given under our signet at my lord's manor of Hampton Court the 12th day of October. Jane the Quene. |

| The following letter was Anne of Cleves's very diplomatic response to Henry VIII's request for an annulment of their brief marriage. Though her brother pressed her to return home to the duchy of Cleves, Anne was content to remain in England. There were two reasons for this - first, Henry was so grateful for her easy submission and gracious manners, he rewarded her with a very comfortable lifestyle. She was able to live as a wealthy dowager and enjoyed a close relationship with the king (now termed her 'brother') and his three children. Secondly, she did not want to face an ignominious return to Cleves. After Henry's public rejection of their union, she would not have found another husband and would have been forced to rely on her brother's generosity. Henry was very impressed by this letter. Its tone of respectful subservience to his wishes inspired his gratitude. Despite his reputation for tyranny, the great king could be kind and generous. Anne had little cause to think ill of him. After all, most historians focus on Henry's feelings in this matter - but perhaps the lady from Cleves was less than enamored with her husband and was equally desperate to escape the marriage. According to all reports, she learned to love English beer and grew plump and happy in her adopted country. | Pleaseth your most excellent majesty to understand that, whereas, at sundry times heretofore, I have been informed and perceived by certain lords and others your grace's council, of the doubts and questions which have been moved and found in our marriage; and how hath petition thereupon been made to your highness by your nobles and commons, that the same might be examined and determined by the holy clergy of this realm; to testify to your highness by my writing, that which I have before promised by my word and will, that is to say, that the matter should be examined and determined by the said clergy; it may please your majesty to know that, though this case must needs be most hard and sorrowful unto me, for the great love which I bear to your most noble person, yet, having more regard to God and his truth than to any worldly affection, as it beseemed me, at the beginning, to submit me to such examination and determination of the said clergy, whom I have and do accept for judges competent in that behalf. So now being ascertained how the same clergy hath therein given their judgment and sentence, I acknowledge myself hereby to accept and approve the same, wholly and entirely putting myself, for my state and condition, to your highness' goodness and pleasure; most humbly beseeching your majesty that, though it be determined that the pretended matrimony between us is void and of none effect, whereby I neither can nor will repute myself for your grace's wife, considering this sentence (whereunto I stand) and your majesty's clean and pure living with me, yet it will please you to take me for one of your humble servants, and so determine of me, as I may sometimes have the fruition of your most noble presence; which as I shall esteem for a great benefit, so, my lords and others of your majesty's council, now being with me, have put me in comfort thereof; and that your highness will take me for your sister; for the which I most humbly thank you accordingly. Thus, most gracious prince, I beseech our Lord God to send your majesty long life and good health, to God's glory, your own honor, and the wealth of this noble realm. From Richmond, the 11th day of July, the 32nd year of your majesty's most noble reign. Your majesty's most humble sister and servant, Anne the daughter of Cleves. |

| This is the only surviving letter written by Henry VIII's fifth wife, Katherine Howard. It was written in the spring of 1541, roughly eight months after she married the king. After Catherine's fall from grace, Culpeper was among the men charged with committing adultery with the queen. It was a treasonable offense, and he was executed for it (along with Francis Dereham.) Culpeper tried to save himself by arguing that he had met with Catherine only because the young queen was 'dying of love for him', and would not let him end the relationship. Catherine, for her part, argued otherwise; she told her interrogators that Culpeper ceaselessly begged for a meeting and she was too fearful to refuse. However, the letter clearly supports Culpeper's version of events. After all, the queen did write 'it makes my heart die to think what fortune I have that I cannot be always in your company.' The affection she felt for Culpeper led to a legend surrounding Catherine's last words - 'I die a Queen, but would rather die the wife of Culpeper.' This final declaration of love did not occur; its invention was an attempt to give Catherine's pathetic and tragic story some mark of distinction. Catherine was not as well educated as Henry's other wives, though her mere ability to read and write was impressive enough for the time. This letter taxed her greatly, as she points out in the closing lines. It is transcribed here as originally written, and the grammatical mistakes are Catherine's own. | Master Culpeper, I heartily recommend me unto you, praying you to send me word how that you do. It was showed me that you was sick, the which thing troubled me very much till such time that I hear from you praying you to send me word how that you do, for I never longed so much for a thing as I do to see you and to speak with you, the which I trust shall be shortly now. That which doth comfortly me very much when I think of it, and when I think again that you shall depart from me again it makes my heart die to think what fortune I have that I cannot be always in your company. It my trust is always in you that you will be as you have promised me, and in that hope I trust upon still, praying you that you will come when my Lady Rochford is here for then I shall be best at leisure to be at your commandment, thanking you for that you have promised me to be so good unto that poor fellow my man which is one of the griefs that I do feel to depart from him for then I do know no one that I dare trust to send to you, and therefore I pray you take him to be with you that I may sometime hear from you one thing. I pray you to give me a horse for my man for I had much ado to get one and therefore I pray send me one by him and in so doing I am as I said afor, and thus I take my leave of you, trusting to see you shortly again and I would you was with me now that you might see what pain I take in writing to you. Yours as long as life endures, Katheryn. One thing I had forgotten and that is to instruct my man to tarry here with me still for he says whatsomever you bid him he will do it. |

| Catherine Parr wed King Henry VIII on 12 July 1543 at Hampton Court Palace. Henry was her third husband and not her personal choice. She was in love with Thomas Seymour, the brother of Henry's third wife, Jane; he eventually became her fourth husband just a few months after Henry's death in 1547. Once the marriage to Henry was settled upon, Katharine worked to make it successful. She was, in all respects, admirably suited to the task. She had experience managing temperamental elderly men and nursing their various ailments. She was very intelligent and committed to scholarship, but she also participated fully in the life of Henry's court. She grew as fond of finery as any of his wives and dressed magnificently. She and Henry grew close. He refused to allow anyone else to wrap his badly ulcered leg; he also made her Queen-Regent while he attended the siege of Boulogne in 1544. This letter was written during that six-week absence and its tone is loving and respectful. In it, Katharine mentions the King of Scotland's widow, Marie de Guise, as well as Henry's three children. In addition to her success as a sixth wife, Katharine was an admirable stepmother who genuinely loved the Princesses Mary and Elizabeth and Prince Edward. | Although the distance of time and account of days neither is long nor many of your majesty's absence, yet the want of your presence, so much desired and beloved by me, maketh me that I cannot quietly pleasure in anything until I hear from your majesty. The time, therefore, seemeth to me very long, with a great desire to know how your highness hath done since your departing hence, whose prosperity and health I prefer and desire more than mine own. And whereas I know your majesty's absence is never without great need, yet love and affection compel me to desire your presence. Again, the same zeal and affection force me to be best content with that which is your will and pleasure. Thus love maketh me in all things to set apart mine own convenience and pleasure, and to embrace most joyfully his will and pleasure whom I love. God, the knower of secrets, can judge these words not to be written only with ink, but most truly impressed on the heart. Much more I omit, lest it be thought I go about to praise myself, or crave a thank; which thing to do I mind nothing less, but a plain, simple relation of the love and zeal I bear your majesty, proceeding from the abundance of the heart. Wherein I must confess I desire no commendation, having such just occasion to do the same. I make like account with your majesty as I do with God for his benefits and gifts heaped upon me daily, acknowledging myself a great debtor to him, not being able to recompense the least of his benefits; in which state I am certain and sure to die, yet I hope in His gracious acceptation of my goodwill. Even such confidence have I in your majesty's gentleness, knowing myself never to have done my duty as were requisite and meet for such a noble prince, at whose hands I have found and received so much love and goodness, that with words I cannot express it. Lest I should be too tedious to your majesty, I finish this my scribbled letter, committing you to the governance of the Lord with long and prosperous life here, and after this life to enjoy the kingdom of his elect. From Greenwich, by your majesty's humble and obedient servant, Katharine the Queen. |

| First of all, this letter may be a fake. Then again, it may not. The debate over its authenticity continues and no definitive answer is possible. The original no longer exists; a copy was said to be found amongst Sir Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex's papers after his execution. Most of Anne's modern biographers believe it to be a forgery. Their reason? They don't believe any 16th century prisoner would have been allowed to write to their monarch in such a familiar manner. Yet Anne was not just any political prisoner - she was Henry VIII's wife and had been his grand passion for several years. Locked away in the Tower, aware of the concurrent arrests of her brother and friends and worried about her young daughter, she may very well have written to the king. She was in a desperate situation, of course, but she also believed (as witnesses attest) that Henry would be merciful and simply divorce her and send her to a convent. She was proven wrong and executed thirteen days after this letter was supposedly written. In debating the authenticity, another point to consider is Anne's personality. Her combative temperament was well-documented by her contemporaries; they observed with awe that she dared to chastise and insult the king. Henry VIII himself commented upon her boldness. It had probably helped to attract his attention. But the appeal of such a passionate and emotional woman did not hold him forever. By the end of their relationship, Henry was comparing her to a shrew and warned her to hold her tongue in his presence. His next wife was the very quiet and meek Jane Seymour, and a more glaring contrast to Anne Boleyn cannot be imagined. If Anne had written a letter to Henry from her prison, it would undoubtedly read exactly like this one. As to its authenticity..... I have included this letter because it is an interesting historical curiosity, whether authentic or forged. It is up to the individual reader to reject or accept it. | Your grace's displeasure and my imprisonment are things so strange to me, that what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant. Whereas you send to me (willing me to confess a truth and so obtain your favor), by such a one, whom you know to be mine ancient professed enemy, I no sooner received this message by him, than I rightly conceived your meaning; and if, as you say, confessing a truth indeed may procure my safety, I shall with all willingness and duty, perform your duty. But let not your grace ever imagine that your poor wife will be brought to acknowledge a fault, where not so much as a thought ever proceeded. And to speak a truth, never a prince had wife more loyal in all duty, and in all true affection, than you have ever found in Anne Bulen - with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself, if God and your grace's pleasure had been so pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forget myself in my exaltation or received queenship, but that I always looked for such alteration as I now find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer foundation than your grace's fancy, the least alteration was fit and sufficient (I knew) to draw that fancy to some other subject. You have chosen me from low estate to be your queen and companion, far beyond my desert or desire; if, then, you found me worthy of such honor, good your grace, let not any light fancy or bad counsel of my enemies withdraw your princely favor from me; neither let that stain - that unworthy stain - of a disloyal heart towards your good grace ever cast so foul a blot on me, and on the infant princess your daughter. Try me, good king, but let me have a lawful trial, and let not my sworn enemies sit as my accusers and as my judges; yea, let me receive an open trial, for my truth shall fear no open shame. Then you shall see either my innocency cleared, your suspicions and conscience satisfied, the ignominy and slander of the world stopped, or my guilt openly declared. So that, whatever God and you may determine of, your grace may be freed from an open censure; and my offense being so lawfully proved, your grace may be at liberty, both before God and man, not only to execute worthy punishment on me as an unfaithful wife but to follow your affection already settled on that party for whose sake I am now as I am, whose name I could some while since have pointed unto - your grace being not ignorant of my suspicions therein. But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my death, but an infamous slander must bring your the joying of your desired happiness, then I desire of God that he will pardon your great sin herein, and likewise my enemies, the instruments thereof; and that he will not call you to a strait account for your unprincely and cruel usage of me at his general judgment-seat, where both you and myself must shortly appear; and in whose just judgment, I doubt not (whatsoever the world may think of me), mine innocency shall be openly known and sufficiently cleared. My last and only request shall be, that myself only bear the burden of your grace's displeasure, and that it may not touch the innocent souls of those poor gentlemen, whom, as I understand, are likewise in strait imprisonment for my sake. If ever I have found favor in your sight - if ever the name of Anne Bulen have been pleasing in your ears - then let me obtain this request; and so I will leave to trouble your grace any further, with mine earnest prayer to the Trinity to have your grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your actions. From my doleful prison in the Tower, the 6th May. |