Edward VI in his own words

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| | The Diary & Letters | |

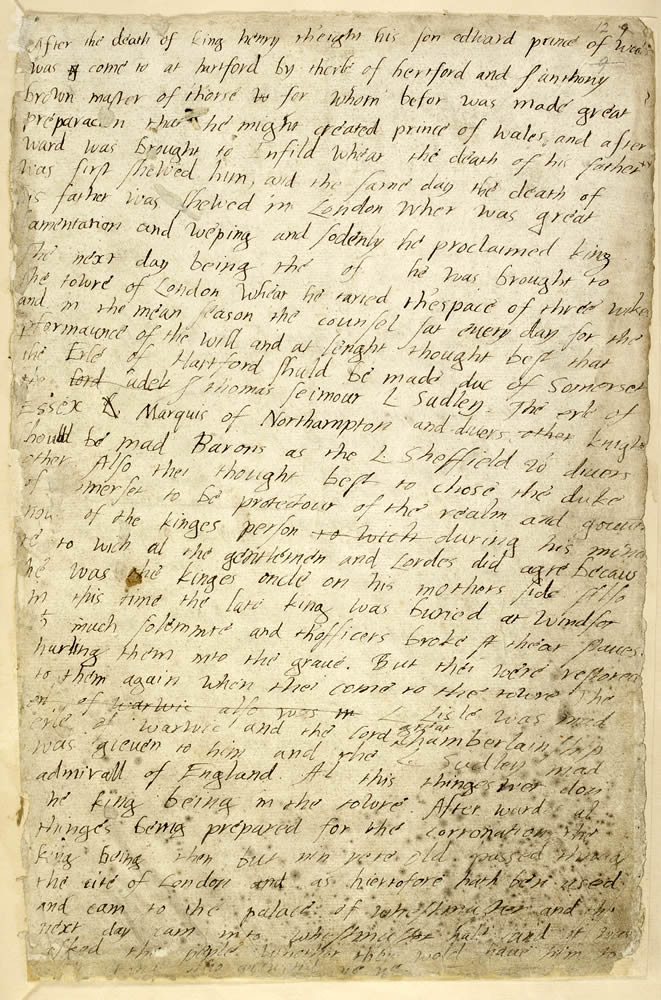

Edward VI reveals here that he and his sister Elizabeth learnt of their father Henry VIII’s death from his uncle Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, at Elizabeth’s Enfield residence on 30 January 1547.Although he writes that it caused great grief in London, he reveals nothing of his personal feelings. He describes the Privy Council’s choice of Edward Seymour as Protector and Governor of the King’s Person and mentions how his father’s officers broke their staffs of office and threw them into Henry’s grave at his burial.Edward may have been prompted to write his ‘diary’ by one of his tutors. It begins with a description of his childhood until 1547. For the years 1547 to 1549 the ‘diary’ is a chronicle of past events that mostly refers to Edward in the third person. From March 1550 until November 1552, when it ends, it is more like a diary, with entries for individual days. [Source: <a class="external" href="http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/henryviii/birthaccdeath/edwardvidiary/index.html" rel="nofollow" target="_blank" title="The British Library">The British Library</a>] |

*Review of England's Boy King: The Diary of Edward VI, 1547-1553. Edited by Jonathan North. Welwyn Garden City: Ravenhall Books, 2005. by Ronald H. Fritze, College of Arts and Sciences, Athens State University: Edward VI (1537-1553) started to keep a sort of daily journal in March 1550 when he was twelve years old. He sometimes called it a chronicle. Initially it had the appearance of an assignment from his tutors, but he appears to have found keeping such a record personally satisfying. At the start of his journal he went back to the beginning of his reign and gave yearly summaries for 1547, 1548, and 1549. After that he attempted to keep a daily record of events. Unlike a true diary, he actually says little about his own daily activities or his personal feelings or opinions. It has been pointed out that none of Edward VI's supposed piety appears in this work. Instead, he comes across as cold, detached, and secular. It is possible that this reflects the limitations of the type of document more than the boy-king's personality. Jousting and wars take up a disproportionate amount of the entries. Basically the young king recorded what others told him about events and one of his most significant informants was the French ambassador |

In his "devise for the succession", Edward passed over his sisters' claims to the throne in favour of Lady Jane Grey. In the fourth line, he altered "L Maries heires masles" to "L Jane and her heires masles" |

King Edward VI's Journal - entry dated 1551: The lady Mary, my sister, came to me to Westminster, where after greetings she was called with my council into a chamber where it was declared how long I had suffered her mass, in hope of her reconciliation, and how now, there being no hope as I saw by her letters, unless I saw some speedy amendment I could not bear it. She answered that her soul was God's and her faith she would not change, nor hide her opinion with dissembled doings. It was said I did not constrain her faith but willed her only as a subject to obey. And that her example might lead to too much inconvenience. On 19 March the emperor's ambassador came with a short message from his master of threatened war, if I would not allow his cousin the princess to use her mass. No answer was given to this at the time. The following day the bishops of Canterbury, London and Rochester, Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley and John Scory, concluded that to give licence to sin was sin; to allow and wink at it for a time might be born as long as all possible haste was used. | Diary entry 1549 In the meantime in England rose great stirs, likely to increase much if it had not been well foreseen. The council, about nineteen of them, were gathered in London, thinking to meet with the Lord Protector and to make him amend some of his disorders. He, fearing his position, caused the secretary in my name to be sent to the lords to know for what cause they gathered their powers together and, if they meant to talk with him, to say that they should come in a peaceable manner. The next morning, being 6 October and Saturday, he commanded the armour to be brought out of the armoury of Hampton Court, about 500 harnesses, to arm both his and my men with it, the gates of the house to be fortified, and people to be raised. People came abundantly to the house. That night with all the people at nine or ten o'clock at night I went to Windsor, and there watch and ward was kept every night. The lords sat in the open places of London, calling gentlemen before them and declaring the causes of accusing the lord protector, and caused the same to be proclaimed. After which time few came to Windsor, but only the men of my own guard who the lords willed, fearing the rage of the people so lately quieted. Then the protector began to treat by letters, sending Sir Philip Hoby, lately come from his embassy in Flanders to see his family, who brought on his return a very gentle letter to the protector which he delivered to him, another to me, another to my household, to declare his faults, ambition, vainglory, entering into rash wars in my youth, negligence about Newhaven, enriching himself from my treasure, following his own opinions, and doing all by his own authority etc., which letters were openly read, and immediately the lords came to Windsor, took him and brought him through Holborn to the Tower. Afterwards I came to Hampton Court where they appointed by my consent six lords of the council to be attendant on me, at least two, and four knights. Lords - the marquis of Northampton, the earls of Warwick and Arundel, lords Russell, Sr John and Wentworth. Knights - Sir Andrew Dudley, Sir Edward Rogers, Sir Thomas Darcy, Sir Thomas Wroth. Afterwards I came through London to Westminster. Lord Warwick was made admiral of England. Sir Thomas Cheney was sent to the emperor for relief, which he could not obtain. Mr Nicholas Wootton was made secretary. The lord protector, by his own agreement and submission, lost his protectorship, treasureship, marshalship, all his movables and nearly 2,000 pds of lands, by act of Parliament. |