Thomas Cranmer - Historical Profile

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| The History of Archbishop of Canterbury Click EasyEdit to update this page! (Don't see the EasyEdit button above? <a href="/#signin" target="_self">Sign in</a> or <a href="/accountnew" target="_self">Sign up</a>.) |

INTERESTING FACTS:

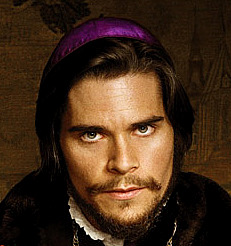

|  in later years "A dithering ecclesiastical Hamlet, an heretical schismatic, and an heroic defender of reformed Christianity, Thomas Cranmer has been vilified and praised with such words by his own and every succeeding generation." - Reverend David Garrett

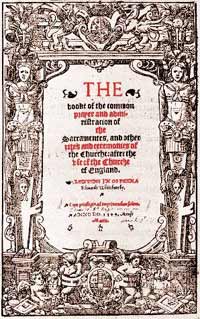

It is generally assumed that the Book of Common Prayer (1549) is largely the work of Cranmer but, as no records of the development of the prayer book exist, this cannot be definitively determined. This prayer book was in use only for three years, until the extensive revision of 1552. However, much of its tradition & language remains in the prayer books of today. It is generally assumed that the Book of Common Prayer (1549) is largely the work of Cranmer but, as no records of the development of the prayer book exist, this cannot be definitively determined. This prayer book was in use only for three years, until the extensive revision of 1552. However, much of its tradition & language remains in the prayer books of today. <embed height="254" src="http://widget.wetpaintserv.us/wiki/thetudorswiki/page/Thomas+Cranmer+-+Historical+Profile/widget/youtubevideo/26b687535831b6d462a5e536c3937ca60787bd46" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="332" wmode="transparent"/> | |

| <embed height="254" src="http://widget.wetpaintserv.us/wiki/thetudorswiki/page/Thomas+Cranmer+-+Historical+Profile/widget/youtubevideo/001d80fb6cc6aa1f1211ac7fac85c39e9e6fbba3" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="332" wmode="transparent"/> | LITERATURE:

| |

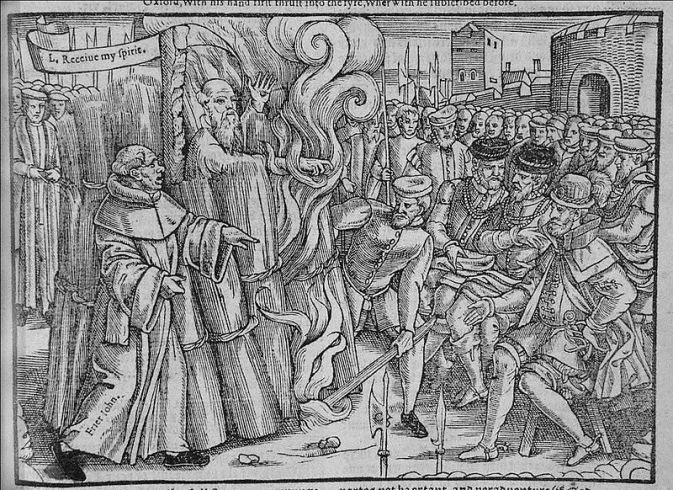

| Controversy: The steps leading to Cranmer's execution were very exceptional since the Marian Church did let people go if they recanted their Protestantism. There hasn't been a case where an individual who had recanted was still sent to the stake. His death was unlawful as under church guidelines a repented heretic who embraced the Church was not to be punished with the flames. Why Mary chose to persecute him is a matter of some debate. Did Mary blame him for her mother's humiliation and the fact that she had been bastardised as it was he who announced the annulment of her parent's marriage? Was it because she saw him a as a figurehead for the Protestant Edwardian Reformation or for political reasons, she saw him as a liability? Did she believe it was her 'duty' to remove him as she felt he was not being sincere in his recantation? Despite her reasons, her decision was unwise as she could have exploited Cranmer's recantation. Instead she made him into a martyr and thus strengthened the Protestant cause. | LINKS:

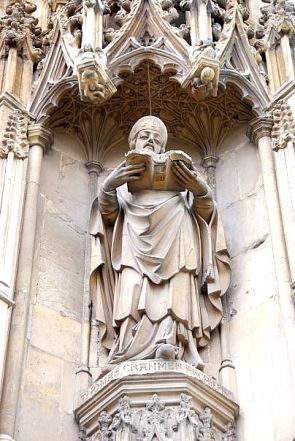

statue of Cranmer from Oxford's Martyrs Memorial | |

|  St Mary’s Church, Oxford. Part of Thomas Cranmer’s trial for heresy took place within this church. He was also taken here prior to his death so he could publicly recant his faith. The middle pillar on the left was where a special platform was built for Cranmer; you can still see where sections of the pillar had been cut away to accommodate for the pulpit. However instead of announcing his recantation, Cranmer took the opportunity to publicly renounce his previous denial and denounced his former rival Stephan Gardiner and the pope. He was pulled down from the pulpit and rushed to the scaffold on Broad Street. [source: Nasim Tadghighi] | |

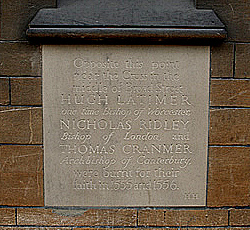

| Stained glass of the martyrdom of Thomas Cranmer, Nicolas Ridley, and Hugh Latimer who were burned at Oxford during the Marian Persecutions. (they were not however, all burned at the same time. Ridley and Latimer burned six months earlier) | See also: Tudor Burials This cross marks the spot on Broad Street, Oxford where Thomas Cranmer was burned at the stake. |

Cranmer's own words:

Letter of Thomas Cranmer on Henry VIII's divorce, 1533In this letter Cranmer writes of the official divorce of Henry VIII from Catherine of Aragon and the coronation of Henry's next Queen, Anne Boleyn. He speaks of the legal meeting in which Catherine was informed that the King rejected the Pope's authority over the marriage and of the obvious pregnancy of Anne at her coronation ceremony. Note the tone of the last paragraph of the letter.Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Mr. Hawkyns the Ambassador at the Emperor's Court; upon the Divorce of Queen Catherine, and the Coronation of Queen Anne Boleyn. 1533. In my most heartie wise I commend me unto you and even so, would be right glad to hear of your welfare, etc. This is to advertise you that inasmuch as you now and then take some pains in writing unto me, I would be loathe you should think your labor utterly lost and forgotten for lack of writing again; therefore and because I reckon you to be some deal desirous of such news as hath been here with us of late in the King's Graces matters, I intend to inform you a parte thereof, according to the tenure and purport used in that behalf. And first as touching the small determination and concluding of the matter of divorce between my Lady Catherine and the King's Grace, which said matter after the Convocation in that behalf had determined and agreed according to the former consent of the Universities, it was thought convenient by the King and his learned Council that I should repair unto Dunstable, which is within 4 miles unto Amptell, where the said Lady Catherine keepeth her house, and there to call her before me, to hear the final sentence in this said matter. Notwithstanding she would not at all obey thereunto, for when she was by doctor Lee cited to appear by [the end of] a day, she utterly refused the same, saying that inasmuch as her cause was before the Pope she would have none other judge; and therefore would not take me for her judge. Nevertheless the 8th day of May, according to the said appointment, I came unto Dunstable, my lord of Lincoln being assistant unto me, and my Lord of Winchester, Doctor Bell... with diverse others learned in the Law being counsellors in the law for the King's part; and so there at our coming kept a court for the appearance of the said Lady Catherine, where were examined certain witnesses which testified that she was lawfully cited and called to appear... And the morrow after Ascension day I gave final sentence therin, how it was indispensable for the Pope to license any such marriages. This done, and after our re-journeying home again, the Kings Highness prepared all things convenient for the Coronation of the Queen, which also was after such a manner as followeth. The Thursday next before the feast of Pentecost, the King and the Queen being at Greenwich, all the crafts of London thereunto well appointed, in several barges decked after the most gorgeous and sumptuous manner, with diverse pageants thereunto belonging, repaired and waited all together upon the Mayor of London; and so, well furnished, came all unto Greenwich, where they tarried and waited for the Queen's coming to her barge; which so done, they brought her unto the Tower, trumpets, shawms, and other diverse instruments all the ways playing and making great melody, which, as is reported, was as comely done as never was like in any time nigh unto our rememberance. And so her Grace came to the Tower at Thursday at night, about 5 of the clock... In the morning there assembled with me at Westminster church the bishop of York, the bishop of London, the bishop of Winchester, the bishop of Lincoln, the bishop of Bath, and the bishop of Saint Asse, the Abbot of Westminster with ten or twelve more abbots, which all revested ourselves in our pontificalibus (robes of office), and so furnished, with our crosses and croziers, proceeded out of the Abbeu in a procession unto Westminster Hall, where we received the Queen apparelled in a robe of purple velvet, and all the ladies and gentlewomen in robes and gowns of scarlet according to the manner used before time in such besynes; and so her Grace, sustained on each side with two bishops, the bishop of Lincoln and the bishop of Winchester, came forth in procession unto the Church of Westminster... my Lord of Suffolk bearing before her the crown, and two other lords bearing also before her a scepter and a white rod, and so entered up into the high altar, where diverse ceremonies used about her, I did set the crown on her head, and then was sung Te Deum, etc.... But now Sir you may not imagine that this Coronation was before her marriage, for she was married much about saint Paul's day last, as the condition thereof doth well appear by reason she is now somewhat big with child. Notwithstanding, it hath been reported throughout a great part of the realm that I married [them after the Coronation]; which was plainly false, for I myself knew not thereof a fortnight after it was done. And many other things be also reported of me, which be mere lies and tales. [Source: From Henry Ellis, ed. Original Letters of Illustrative of English History, including Numerous Royal Letters. London: Harding, Triphook, and Lepard, 1825. Vol 3, pp. 34-39. Archaic spellings in places have been reduced to make it easier to read] |