FALCONRY on the Tudors

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

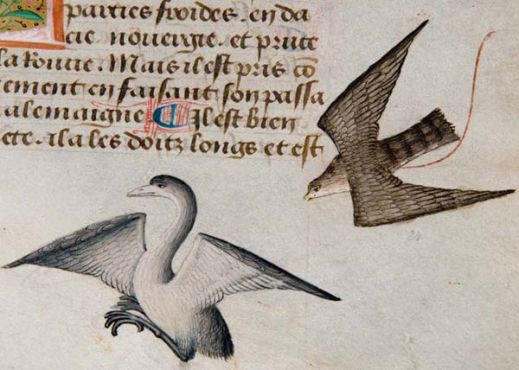

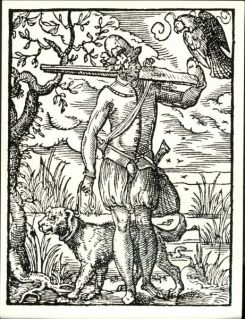

Falconry & Hawking in Tudor Times | Falconry, like hunting, was a sport developed from a necessity-- the need to provide meat for the table, especially in winter and spring, when it was not wise to slaughter stock from the farm. It is the use of specially trained falcons and hawks to capture birds or small mammals. Practised since ancient times in the Middle East, falconry was introduced from continental Europe to Britain in Saxon times. |  A falconer by Hans Holbein c.1542 |

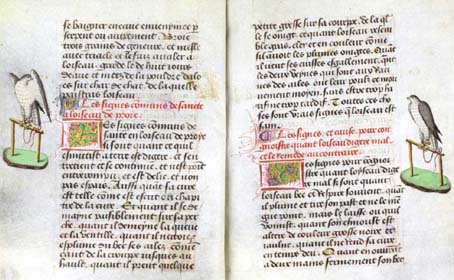

In 1486 . The Book of Hawking, Hunting, and Heraldry attributed to Dame Juliana Berners, prioress of Sopwell Priory was published by St. Albans: Schoolmaster Printer and became wildly popular in the 16th century. It contains three essays, on hawking, hunting and heraldry and went through many editions, quickly acquiring an additional essay on angling (fishing). Commonly it is known by titles such as "The Book of Hawking, Hunting, and Blasing of Arms". It is one of the early works of the Printing Press and could be called a "best seller" by today's standards showing how popular the sport was. |  |

<embed allowfullscreen="true" height="385" src="http://widget.wetpaintserv.us/wiki/thetudorswiki/widget/youtubevideo/aa2f401aceb22220805c5eee5600bfed3746d66d" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="480" wmode="transparent"/> |

|

The period of 500 A.D. to 1600 A.D. saw the peak of interest in falconry. The period of 500 A.D. to 1600 A.D. saw the peak of interest in falconry. It became a highly regulated, revered and popular sport among nearly all-social classes in Europe. In Western Europe and Great Britain, falconry went beyond being a sport of royalty or being practiced as a necessity. Instead, its popularity became what sociologists would term a craze or fad, and became a status symbol in medieval society. The sport was most popular among the upper class citizens in Europe, especially among the clergy, who were noted for their fondness for falconry. Pope Leo X was an avid falconer, who went on frequent hunting excursions with his birds. In some religious orders, falcons were even taken into religious services, so much so that nuns, many of whom during this time were rarely seen without their falcons on their wrists, were reprimanded for bringing their birds into the chapel by bishops, who complained the practice interfered with the services. So important was falconry to English society that one could rarely walk down the streets of medieval England without seeing someone with his or her falcon perched on hand on wrist. A fourteenth-century lady was advised by her husband to take her bird everywhere with her, including church, so that it would become accustomed to people.

|

During the Middles ages and at the height of the popularity of falconry, the birds used had their own hierarchy. Certain birds which were rarer and more expensive were considered only suitable for higher ranking persons. The ‘emperors’ of birds were the eagle, vulture or merlin. Then came the peregrine falcon, goshawk and sacre. Further down the list the last in precedence, the kestrel known as the ‘knave’ or ‘servant’, suited to ordinary working people. The Boke of St Albans recommended which classes of people should be allowed to own which bird, with the higher ranking birds reserved for royalty alone further down the list. It was considered a crime to be caught hunting with a bird meant for someone more worthy and severe punishments were dealt if caught. The punishment for harming a birds nest, eggs or young were fairly severe but graduated depending on the crime. For example to destroy a falcons eggs meant one year in prison, and to poach a falcon from the wild was reason enough for the criminals eyes to be poked out. The punishment for holding a bird above your social rank was usually the cutting off of the offenders hands. This was usually a sufficient deterrent to the crime. The golden age of falconry ended with the invention of the firearm, its popularity quickly gained and soon falcons and other birds of prey were persecuted to the point of virtual extinction of some species. However as falcons were held in such high regard in England, it was the first place in the world to introduce laws aimed at protecting them and other wild birds of prey. Social Rank & Appropriate Bird |

Golden Eagle |  Peregrine Falcon |  Common Kestrel |  Sparrowhawk |  Merlin |

Anne Boleyn chose the Symbol of the crowned falcon holding a sceptre on a tree stump with red and white flowers sprouting. The white falcon was derived from the heraldic crest of the Earls of Ormonde as her father had been recognized as the heir. The Heraldic meaning of the Falcon/Hawk is One who does not rest until objective achieved. The falcon or hawk signifies someone who is hot or eager in the pursuit of an object much desired. It is frequently found in the coats of arms of nobility from the time when the falcon played an important social role in the sport of kings and nobles. It is found as a heraldic bearing as early as the reign of King Edward II of England. It was also later adopted by her daughter Queen Elizabeth I.

| In this scene in the first season where Anne Boleyn is talking to her father, Sir Thomas Boleyn, there is a hawk in the courtyard which he carries for a while. It is a Harris Hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus) which is an American breed, unfortunately not known in England in the 16th century. See also : Hidden Meanings on the Tudors |

|  |

|  |

SOURCES:

|